The Corinna Posts 4: Memorializing the Memorialist

Sometimes I write about my oldest friend who died of cancer last year. You can find the other Corinna Posts here.

*EMERGENCY ALERT: It is Friday afternoon and I am…wait for it…DELAYED AT DCA. Please send thoughts and prayers, light candles, cast spells, throw salt over your shoulder, pour out a glass, drink a glass, or do whatever you do so we can interrupt this pattern and get me home.*

It is April, and “Boulder to Birmingham” is stuck in my head. I’ve listened to Emmylou Harris sing it more times this week than I’m willing to tell you. I’ve listened to other people sing it (Starland Vocal Band, Dolly, The Hollies, The Wailin’ Jennys, Jessie Buckley).1 I’ve hummed and sung the bits I know. Yet it took days of obsession for me to realize that “Boulder to Birmingham” is an elegy for a friend.2 Like “Lycidas,” it is essence of loss rather than portrait of the lost. But rather than Puritan England poetry loss, it is roaming America at once escaping and looking for loss, which is what Corinna was doing in the last two years of her life, except she was looking for life and escaping loss.

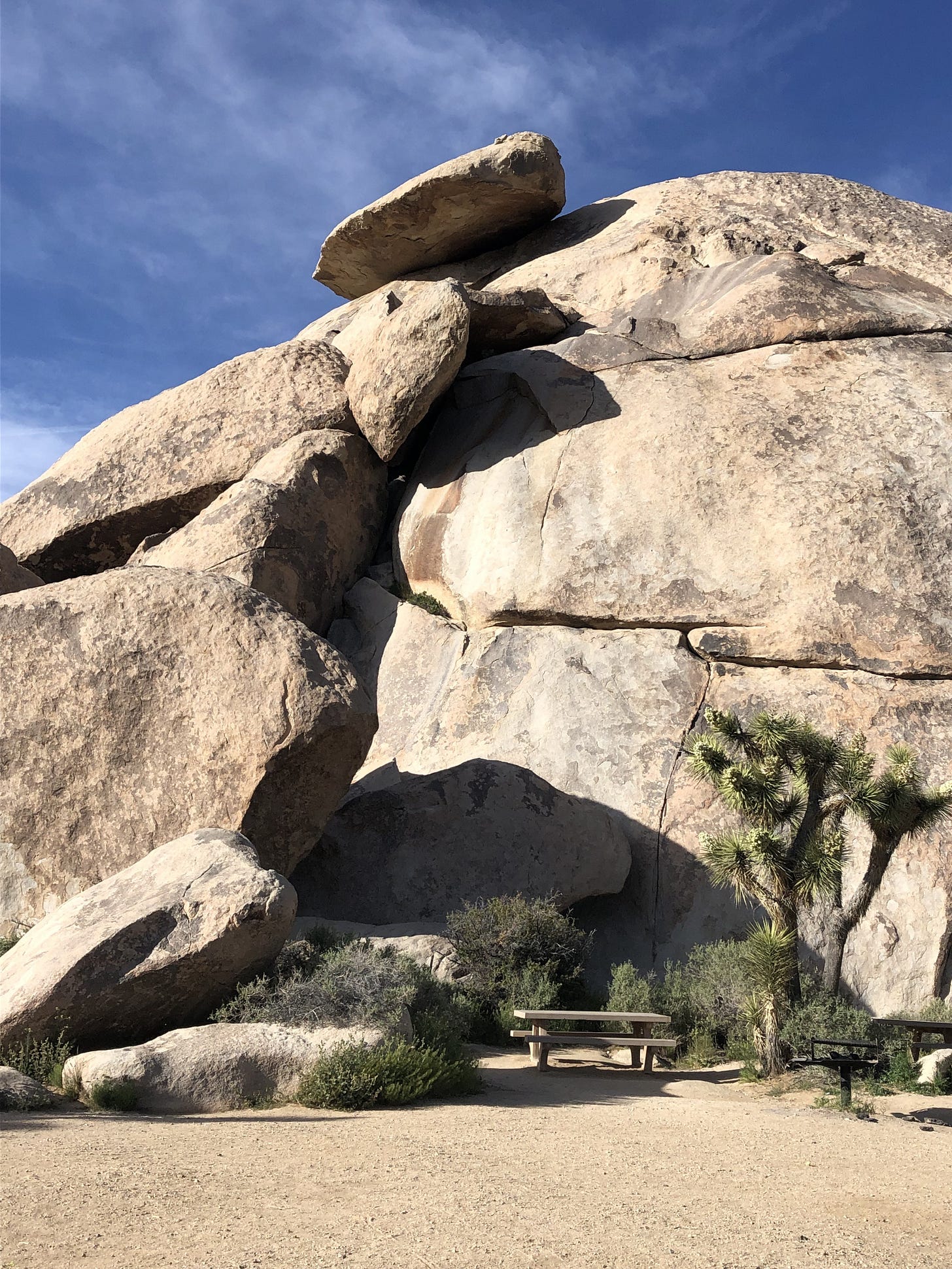

It is April, when we seem to travel. One April, when my children were much younger but old enough, I took them to London to see my father and we visited Haworth in Yorkshire, home of the Brontës. In more recent Aprils, we’ve been to Key West, Palm Springs and Joshua Tree, Utah, and the Blue Ridge Parkway. I realized that we went to all these places in April as I was trying to remember when I first heard “Boulder to Birmingham.” I think it was on a long car ride. I don’t think it was Joshua Tree, though that would have made geographic and cultural sense. I feel like it was Utah, where I was both ecstatically happy and distinctly sad,3 so grabbing onto “Boulder to Birmingham” would have made emotional sense. But really I don’t remember. When we travel, we often drive a lot, we always walk and hike, sometimes we swim or at least wade or look at waterfalls or at least fountains, we eat, we see art, we embrace tourist attractions, and almost always there is a memorial element. In Haworth, we paid our respects at the Brontë family vault and walked out to Top Withins, the ruin said to be the original Wuthering Heights. In Key West, I plotted our own private walking tour to the homes of Elizabeth Bishop, James Merrill, Tennessee Williams, and Hemingway (because you can’t not, though I didn’t really care if we did). We went to Joshua Tree because it’s a place to go, but also Gram Parsons. In Utah, I cried over the abandoned old homes by the side of the road and the families who once inhabited them. Then I cried over the native people they displaced. On the Blue Ridge Parkway, we stopped at every historical site we passed. I am a constitutional memorialist

It is April, and I read Yiyun Li’s New Yorker essay about losing both her sons to suicide. Then I read Where Reasons End, the novel she wrote about her older son in the two months after he died. She’s coming out with a memoir about her younger son next month; he died last year. She says she wrote a novel about Vincent because he was fully legible to her, but a book about the conversations between a dead son and his mother had to be fiction; Where Reasons End is a tersely beautiful elegy about the lost. She wrote a memoir about James because he was unknowable. I wonder if it will be about the lost or the loss or the exponential doubling of loss. Li is someone who needs to write in order to be in the world. I am someone who needs to probe the worst thing possible in order to hold myself apart from it. Is that related to having a memorial constitution?4

It is April, Corinna died a year ago this week, and it only just hit me that she was the ultimate memorialist. She wrote a dissertation on Lithuanian memorials and devoted a huge part of her life to memorializing past Lithuania, which her mother and grandparents fled during World War II. After a couple of years in Germany, they ended up in New York - hence, Corinna - in a cascade of trauma that didn’t stop. Corinna’s passion for Lithuanian and Macedonian music, which she played, performed, and taught for decades, was memorial as joyful life: keeping the music alive, living in the music, passing the music on. Her efforts to preserve the legacy of her grandfather, Lithuanian author Antanas Skema, was memorial as constant struggle: against unauthorized productions of his plays and pirate editions of his books (memorials she couldn’t control), trying and failing to find an institution that would take his library (the world that didn’t care). But a fight always gave Corinna life. Then there was her house, where she kept her parents’ and grandparents’ possessions, her collection of food packages, the drawers and bins that held every piece of paper that had ever passed through her hands; where she papered the walls with old photos and children’s drawings, ticket stubs and souvenirs, postcards and prints.5 Corinna held onto everything, merging memorial and life. Then she held onto life so hard as she was sick and dying, even once she had accepted that she was going to die.

It was April last year when we sat on her bed and laboriously captured her last thoughts about her own memorial. She scribbled a list of what she wanted in one of her 40 million thousand notebooks and then couldn’t read her writing. I couldn’t read it either. She couldn’t come up with the names of the musicians and songs she wanted us to play, but I finally pieced them together with the help of google. She said again what she had already said and didn’t remember saying it. She changed her mind. I finally got a list on my phone. She checked it, approved, and lay down for a nap. She died six days later. We did everything on the list at her memorial in June, but it didn’t bring her back to life.

It is April, and I can’t seem to stop memorializing Corinna, even as capturing her in words feels like it distances her from me. I’m not sure I want to be this kind of constitutional memorialist. But I don’t know what else to be.

I’m not saying

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

But I’m not not saying it.

The Way We Live Now

In the last Trump administration I was notorious for my admiration of Kellyanne Conway (don’t start working up your objections until you’ve clicked on the link, where I address them straight on). This Trump administration, I’m in awe of Karoline Leavitt. She’s out there all day long, always up on exactly what just happened with exactly the spin she needs, holding the line no matter how absolutely bullshit it may be, coming right back at anyone who comes for her - and she’s 27 years old and a new mom to boot. The woman has brains and skills, and she’s doing her job incredibly well, even if her job is obfuscating on behalf of the antichrist. I’m impressed.

Because we still deserve nice things…

Looking out the window on airplanes. That’s it. That’s the nice thing.

So many varieties of sky. So many versions of cloud. Forests, mountains, lakes, rivers, tiny towns, sprawling cities, geometric farmscapes. The other day, minutes after taking off, I looked down on Nantasket Beach stretching out into the ocean and flew low over the beach house I visit every summer, where I could see each landmark and cove. On our descent, the sun was red at the horizon, and the river to my right glowed red as we approached it and subsided to blue as we passed, while the mansions hunkered in the trees, impassive to the changing skies above.

Choose the window seat! Resist the shades-down imperative! Look up from your laptop, kindle, or movie! There’s a whole world out there, and we deserve it.

They are in chronological order, but if you want to listen to one cover, I suggest The Hollies. If you want another, I’d say Jessie Buckley. Though really you won’t go wrong with any of them.

Gram Parsons overdosed in Room 8 of the Joshua Tree Inn on September 19, 1973. His friends stole a hearse and the coffin with his body, drove out to the desert, and set the coffin on fire next to Cap Rock in what is now Joshua Tree National Park. Emmylou Harris, his singing partner, wrote “Boulder to Birmingham” in his memory; it was the only song she wrote on her 1975 album, Pieces of the Sky.

Corinna was back in treatment, which we didn’t know would be nonstop from then on, with occasional palliative breaks, and I had just learned that my favorite musician had the same cancer she had. He’s still playing shows and I am nothing but happy for him.

Is all our grief the same? Or is any grief an endless echo of all the grief? Li asks, “Orphan, widow, widower, I thought, but what do you call a parent who’s lost a child, a sibling who’s lost a sibling, a friend who’s lost a friend?” I said “we lack cultural apparatus” for the death of a friend. A friend who has lost a friend is not a parent who has lost a child, but we share a certain illegibility, the one perhaps because it is not enough, the other because it is absolutely too much.

I wrote, “I first wrote my oldest friend died 11 months ago, but that’s not quite right, for it’s really 11 months and five days, which could also be phrased as 11 months and a bit. Then I wondered how that was really different from a year. I tried last year, but that was too indeterminate (three months? 14 months?), and nearly a year, but that sounded like it was hiding something. I landed on a little less than a year, which is essentially the same but felt more accurate, perhaps because nearly sounds like I am excited to get there, whereas a little less better captures my fear of getting there. The comparison, of course, is babies, whose age we start out describing in days - she’s three days old, five, eight - and then chronicle in weeks - three weeks, seven weeks, 11, maybe even 19 if we’re compulsive. Though we might make it to 15 or even 18 months, we’d never say a child is 35 weeks or 49 months old. I don’t know if the cutoff is when the number gets too big, regardless of the units, or if it’s simply two years, at which point we live the rest of our lives in years, often augmented for children, but never adults, with halfs or quarters. In other words, how we count time passing - days, then weeks, months, and finally years - is another way death is like birth, except birth is an ongoing emerging and death an ongoing receding. In this context, to say a little less than a year, rather than nearly a year, staves off, for at least a little bit longer, the imminent anniversary of Corinna’s death, which will take her that much farther away from us.”

Li writes, “A dear friend says we only count days and weeks and months with this intensity for two reasons: after a baby’s birth, and after a loved one’s death. Three months feel as long as forever, yet as short as a single moment when it’s now and now and now and now, so I must tell my friend there is a difference between life and death. A newborn grow by hour, by day, by week. The death of a child does not grow a minute older.”

Li writes, “Everywhere I turn in the house, there are objects: their meanings reside in the memories connected to them; the memories limn the voids, which cannot be filled by the objects.” But I’m not sure that was exactly the case for Corinna, who was deeply committed to the objects filling the voids, though of course Lacan (always Lacan). But also so many of her objects were memorials of her own life, the life she was still living until she wasn’t. I haven’t been to her house since the day of her memorial.

Such a perfect song. I hope your delay was not like your last delay. I’m writing this in an uber from Bridgewater to Logan headed home after a week here helping my mom, and I’m having an allergic reaction to the air freshener and checking my flight status obsessively, wishing this trip could have been for a different purpose and digesting the fact that I’ll be back soon and again. Really need to find someone near Bridgewater with a spare apartment willing to rent to me for 1990s prices! I love how you write sentences. My punctuation is a nightmare. This air freshener is a crime.

I didn’t know that song before (Boulder to Birmingham) but I just played it (and will definitely play it again) and Mark said it reminded him of Tear-Stained Eye so I listened to that and was introduced to Son Volt, who I’m sure you know even though I didn’t. And I hope you are no longer delayed at DCA!